Penny Siopis (1953), Blush: Panic (detail), 2005, mixed media on paper, 244 x 112cm

SELVES

For this exhibition at the SABC in Auckland Park in 2015, we took a turn inwards to focus on the private and psychological aspects of human identity. While Aluta Continua (2012–2014) focused on public/political realities, and the social theme of predicament ran through Making Waves (2004–2007), this exhibition ventured into the terrain of the self. Personal experience was foregrounded through a selection of works that explore metaphysical states of consciousness and raise questions concerning the status of the individual in relation to the collective.

The binary of self and other is one of the most basic theories of human consciousness and identity – key to how the modern individual comprehends who/what they are, by recognising who/what they are not. Yet a wide range of contemporary critical thinkers have argued for the need to go beyond this binary consciousness, which bears the legacy of Enlightenment thinking, and explore a spectrum of relatedness in which we are constantly occupying and negotiating a plethora of socially constructed identity positions.

In questioning the constructedness of race and gender, new forms of subjectivity have emerged, which are radically different from the self-contained, sovereign subject that was formulated within the Western tradition. Subjectivity is understood to be heterogenous, ambivalent, plural and grounded in multiple identities and social positions, which unsettle the binary construct of ‘self’ in relation to its ‘other’.

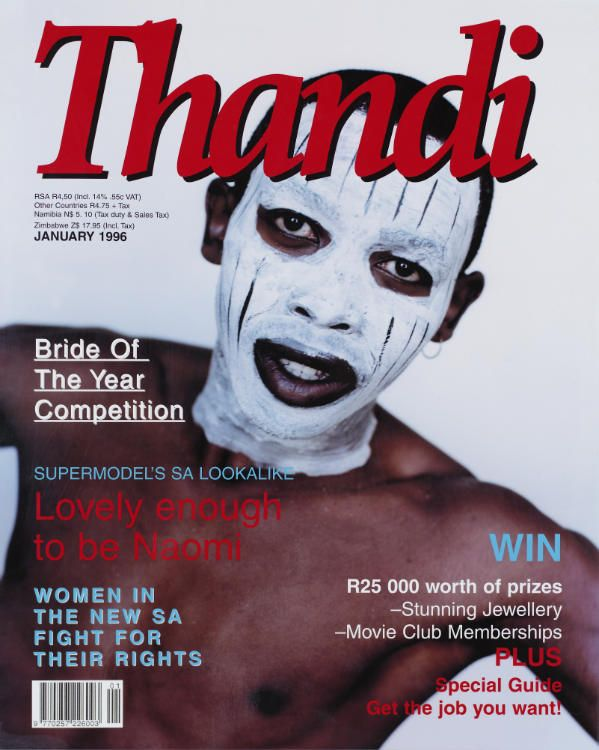

Thembinkosi Goniwe (1971)

Thandi

1999

poster/digiprint

120 x 150cm

Tracey Rose (1974)

MAQE11

2022

lambda photograph

edition: 2/6

118 x 118 cm

Some of works on this exhibition were self-portraits (Adams, Kentridge, Rose) or portraits of others (Tillim, Hugo, Goldblatt, Marasela). The boundary between ‘self’ and ‘other’ was also brought into question, as in Mofokeng’s spirited portrait of his brother, in which the photographer is so tangibly at one with his subject that the image blurs the line between portrait and self-portrait. This theme was further explored with works that embody abstract projections of self into other characters/personae (Rose), beings (Preller, Oltman, Battiss, Siopis, Bell, Geers), creatures (Mason, Legae), objects (Victor, Mntambo, Kumalo, Murray), situations (Shilakoe, Nthodi, Alexander), or even afterlives (Botha). Each artwork evidences an intimate struggle – an internal dialogue made visual.

All of these works were selected for their emphasis on the self in isolation or in self-conscious relation to others. Works by Nhlengethwa, Feni, Alexander and Shilakoe examine the self in relation to groups, while works by Victor and Page explore solitary states of being – intimate struggles of self with self. Other works, like Schreuders’ Mingle, hover somewhere in between. Although the figure depicted is isolated, the title gives the sense that she is on her own in a crowd. Her wine glass alludes to the fact that she is at a social event, and yet she is strikingly alone against a stark white background that might even be the white cube of the art gallery. Similarly, in Faceless by Dumas, the group is implied by the action of the solo figure depicted; although naked, she covers up her face and breasts in a gesture of shame, hiding herself from the gaze of the onlooker. The implied judgment of the group is offset by the potential for intimacy, closeness and acceptance of difference, as portrayed by Walter Battiss in Friends and Feni in A Couple Engaging.

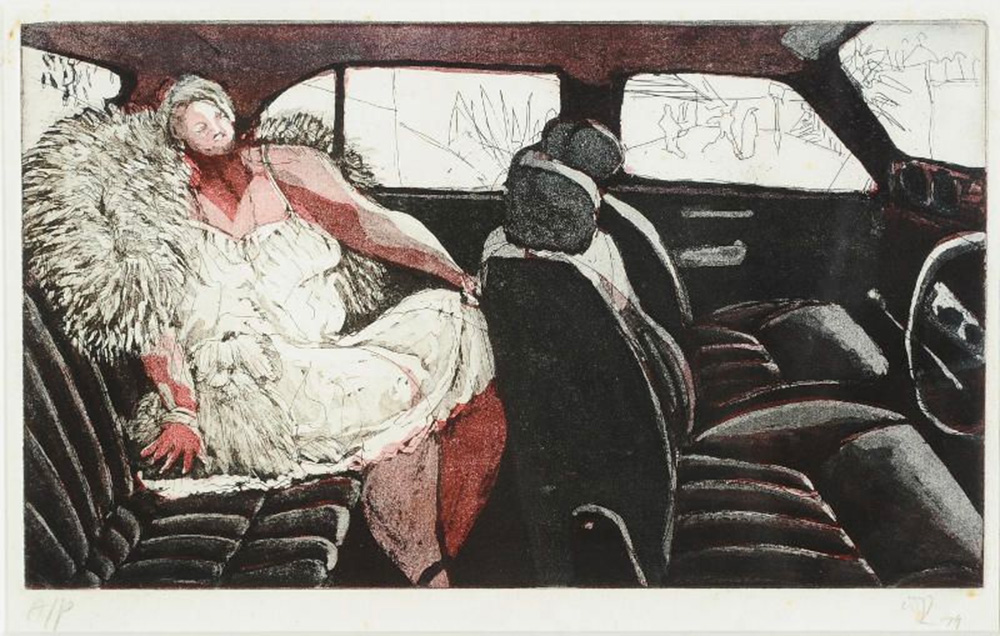

William Kentridge (1955)

Car Interior

1979

etching

13 x 24cm

The capacity for the individual to be subsumed by the violent tendencies of the group is brought starkly to consciousness by Goldblatt’s Fifteen-year-old Lawrence Matjee after his assault by the security police and Alexander’s menacing photomontage, By the end of today you’re going to need us, a work which was produced in 1985 at the height of the police brutality that took place in the dying years of apartheid. Van der Merwe’s Trappings, Tillim’s portrait of a Congolese boy solider in training and Motau’s Emaciated Miner confront the viewer with the documented reality of individuals being instrumentalised by military/industrial systems over which they have limited personal control.

The complexities of cultural identity are brought to the fore by the resurfaced archival studio portraits from The Black Photo Album/Look At Me: 1890 1950 series, in which Mofokeng analyses the sensibilities, aspirations and self-image of black South Africans in times of colonial rule, and peoples’ desire for representation and social recognition.

Other works explore the dynamics of desire and the potential of the self to melt into another in states of longing or obsession. Madikida’s Virus I and II and Van den Berg’s Skin and Ghost series are meditations on the capacity for a virus to redefine one’s intimate sense of physical bodily boundaries. In Hairdo, Page grapples with the physical in relation to the metaphysical – the amount of personal energy humans invest in outward appearances and how absurd daily rituals might relate to the more strange and intimate worlds we inhabit in our dreams. Mystic selves, shadow selves and the personification of personal fears are addressed in works by Hodgins, Bell, Siopis, Preller and Nthodi, while the power of belief is both interrogated and embodied by Geers and Victor.

The works that were included this exhibition might be understood as refrains, notices of various states of existence, sometimes edging toward hysteria or personal dilemma in relation to the multiple states and tensions of being we negotiate as humans.